Africa will remain vulnerable to inflation shocks unless it reduces import dependence, broadens its production bases, and strengthens monetary and fiscal credibility.

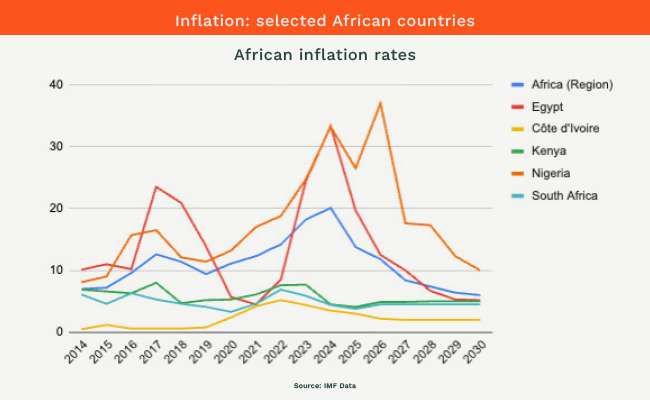

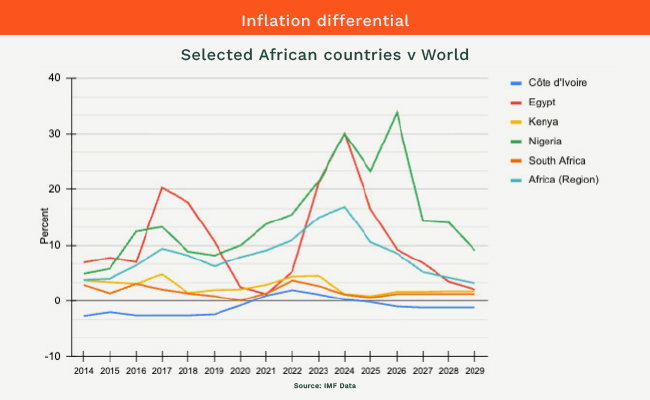

African inflation is spotty and varied, but on average it has been on a downward trend over the past few years, recalling the halcyon days of the 2010s, when the inflation differential with the rest of the world narrowed dramatically.

Sub-Saharan inflation fell from 9.39% in 2022 to 6.7% in 2023, then further down to 4.24% in 2024, which is very good news for the holders of African bonds. “Africa-wide” inflation has come down from 14.5% to 9.5% this year, but this is mostly because of a high inflation base in Egypt, Nigeria and Ghana.

From a longer perspective, the difference between inflation rates in the developed world and those in Africa blew out during the Covid period, but the “convergence trend” is now coming back fast, and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), somewhat hopefully, sees the differential declining to historic lows by the end of the decade.

However, talking about continental averages can be very misleading, according to Paul Robinson, portfolio manager and head of Africa research at Laurium Capital. In most cases, you have to go country by country. The African average is often distorted by some countries which have very high inflation, and recently the most egregious culprits have been Ghana, Zambia and Nigeria and Egypt.

As the key drivers of inflation have been currency weakness, and to a lesser degree energy prices, the outlook will also to a large degree depend on whether currencies stay stable or weaken, as well as, to a lesser degree, food and energy prices. “If the dollar strength is a thing of the past, as many are predicting, it will be easier for African currencies (and thus the inflation outlook) to stabilise for a while,” he says.

On the other hand, some regions have managed their inflation pretty well, notably in West Africa. Even East Africa, something of a problem recently, seems to be under control, “as long as the currency doesn’t blow out sustainably”.

“Ghana is on the way down and should probably, hopefully hold on, and with a bit of luck, Egypt and Nigeria will get there,” Robinson says.

Currently, while inflation has come down in Africa on average and even though some Sub-Saharan countries are seeing improvements, the regional average still exceeds that of advanced economies by a noticeable margin – especially if you count the very high inflation countries.

But remarkably, the IMF is predicting that this trend will continue aggressively for the next five years into something that looks vaguely like inflation alignment.

The problem, says Robinson, is that Africa has a whole bunch of structural issues working against the consolidation theory, most obviously that African countries tend to import more than they export. That puts a constant pressure on the balance of payments. African inflation, says Robinson, is very closely linked to the foreign exchange market, because of this exchange rate vulnerability.

There are other issues too, most obviously commodity price exposure. In many African countries, food accounts for 30%-50% of household expenditure. This makes inflation highly sensitive to harvests, droughts and global grain prices.

Oil importers face large swings in domestic fuel prices, while oil exporters can see boom-bust cycles in government spending that fuel inflation volatility.

There is also weak monetary policy transmission, because the independence of the central banks is often dubious, so the sway of the central bank can be limited. This is compounded by generally shallow capital markets: few long-term savings instruments mean policy rate changes have limited effect on credit conditions.

There are also problems on the demand side. Young, fast-growing populations put constant upward pressure on food demand and urban rents. Large informal sectors make prices harder to monitor and inflation expectations harder to anchor – policy announcements have less influence on behaviour.

Still, a lot of this is changing, which is partly why the IMF is suggesting a convergence trend. Broadly, there has been progress since the 1990s, reflecting better policy frameworks, lower fiscal monetisation, the more widespread adoption of inflation targeting and improved foreign exchange management.

But until African economies reduce import dependence, broaden their production bases, and strengthen monetary and fiscal credibility, they will remain more vulnerable to both global and domestic inflation shocks than the developed world.

Article from Currency